Impacts of Native American gaming can be positive or negative, depending on the tribe and its location. In the 1970s, various Native American tribes took unprecedented action to initiate gaming enterprises.[1] In doing so, they created not only a series of legal struggles between the federal, state, and tribal governments, but also a groundbreaking way to revitalize the Native American economy. Native American gaming has grown from bingo parlors to high-stakes gaming, and is surrounded by controversy on many different levels. Disputes exist concerning tribal sovereignty, negative effects of gaming, and a loss of Native American culture.[2] In the United States, the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act was passed in 1988 to secure collaboration between the states and tribes and also for the federal government to oversee gaming operations. Native American gaming has proven to be extremely lucrative for several tribes, but it has also been unsuccessful in some instances. Native American gaming is contingent upon and only beneficial to its respective reservation.[3]

Success[edit]

- Native American gambling is a specific endeavor and refers to casino-style operations, bingo halls and other forms of gambling, conducted in Indian reservations or other tribal lands across the United States. Since the state governments are restrained in prohibiting such activities in these territories, as postulated by the 1988 Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, all tribal.

- In 2019, tribes created $35 billion in casino-based revenue. So, casinos are central to tribal economic planning, but it comes with a catch: only a handful of them truly sustain those economies.

- According to the authors, payments from the tribes were estimated to be in excess of $350 million in 2002, and 'effectively prevented the state from granting a license for a proposed non-Indian casino in the Bridgeport area.' Nationwide, 'half of the Indians on or near reservations now belong to tribes that have opened Las Vegas-style casinos.'

Gaming can be extremely successful because it stimulates the economy, increases tourism to reservations, reduces unemployment, raises incomes, and increases tribal independence while reducing dependence upon welfare. It has created over 300,000 jobs in the United States.[4] Tribes in only 30 states are eligible to operate gaming enterprises because 16 states have no federally recognized tribes, and five states (Massachusetts, Texas, Missouri, Rhode Island, and Utah) prohibit Native American gaming.[5] 224 of the 550 tribes in 28 states operate the 350 Native American gaming enterprises nationwide,[6] and 68% of Native Americans belong to a tribe with gaming operations.[1] According to the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development, these enterprises earned $19.4 billion in 2005.

Tribes are sovereign nations but are following advice from U.S. States and the federal government to slow the virus' spread. That means shutting American Indian casinos which employ a combined. Some tribes have multiple reservations allotted to them, while around 200 of the nation's 550+ recognized Indian tribes have no land at all. Revenue – While Las Vegas and Atlantic City would hate to admit it, the annual revenue from casinos on Indian reservations exceeds the combined totals for gaming in both cities. In 2009, for example.

Success[edit]

- Native American gambling is a specific endeavor and refers to casino-style operations, bingo halls and other forms of gambling, conducted in Indian reservations or other tribal lands across the United States. Since the state governments are restrained in prohibiting such activities in these territories, as postulated by the 1988 Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, all tribal.

- In 2019, tribes created $35 billion in casino-based revenue. So, casinos are central to tribal economic planning, but it comes with a catch: only a handful of them truly sustain those economies.

- According to the authors, payments from the tribes were estimated to be in excess of $350 million in 2002, and 'effectively prevented the state from granting a license for a proposed non-Indian casino in the Bridgeport area.' Nationwide, 'half of the Indians on or near reservations now belong to tribes that have opened Las Vegas-style casinos.'

Gaming can be extremely successful because it stimulates the economy, increases tourism to reservations, reduces unemployment, raises incomes, and increases tribal independence while reducing dependence upon welfare. It has created over 300,000 jobs in the United States.[4] Tribes in only 30 states are eligible to operate gaming enterprises because 16 states have no federally recognized tribes, and five states (Massachusetts, Texas, Missouri, Rhode Island, and Utah) prohibit Native American gaming.[5] 224 of the 550 tribes in 28 states operate the 350 Native American gaming enterprises nationwide,[6] and 68% of Native Americans belong to a tribe with gaming operations.[1] According to the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development, these enterprises earned $19.4 billion in 2005.

Tribes are sovereign nations but are following advice from U.S. States and the federal government to slow the virus' spread. That means shutting American Indian casinos which employ a combined. Some tribes have multiple reservations allotted to them, while around 200 of the nation's 550+ recognized Indian tribes have no land at all. Revenue – While Las Vegas and Atlantic City would hate to admit it, the annual revenue from casinos on Indian reservations exceeds the combined totals for gaming in both cities. In 2009, for example.

As compared to the $4.5 billion earned by Native American gaming revenues in 1995, these enterprises have shown substantial growth in just 10 years. These enterprises, earning $19.4 billion a year, account for 25.8% of the nation's $75 billion revenue (brought in by the total gaming enterprises in the country).[1] In addition, Native American gaming is the source of 400,000 jobs, and the profits from the enterprises often go toward programs that create jobs.[6] For example, 75% of the profit generated by Cherokee Nation Enterprises in 2005 was given to the Jobs Growth Fund, which expands businesses within the Cherokee Nation to create more jobs.[7]

Revenues, by law, must go toward improving reservation communities. The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act requires that revenues go toward tribal government operations, promotion of the welfare of the tribe and its citizens, economic development, support of charitable organizations, and compensation to local non-Native governments for support of services provided by those governments.[1] Tribes have boosted their socioeconomic status in the past several years by improving their infrastructure, but due to the lack of federal and state funding, have only been able to do so as a result of gaming enterprises. For instance, tribes often build casino-related facilities that draw visitors such as hotels, conference centers, entertainment venues, golf courses, and RV parks.

Once a reservation has established a strong economic foundation, it can draw in businesses that are unrelated to gaming. A common trend is that casinos stimulate the economy, and other business sustain it. For instance, the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians built in a water-bottling plant on the reservation, and along with three other tribes, invested in a hotel in Washington, DC. The Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska is involved in a number of businesses, some of which are internet media, home manufacturing, used autos, and gas stations. The Morongo Band of Mission Indians, a small band in California, has opened a Shell station, A&W drive-in, Coco's Restaurant, a water-bottling plant, and a fruit orchard operation. In addition to involvement in private corporations, Native nations have enough sustainability to bolster government programs. Some of these projects include, but are not limited to: providing law enforcement, fire fighters, schools, translators for emergency response, college scholarships, assistance with mortgage down payments, protection for endangered species, monitoring for water quality, care for elders, police cars, foster-care improvements, and health clinics.[1]

Tribes sometimes distribute funds on a per capita basis to directly benefit its citizens.[8] Because these have sometimes shown negative effects such as a dependence on tribal government, low attendance in school, and an unwillingness to work, some tribes have experimented with decreasing per capita payments as punishment. To clarify, the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation Tribal Council deducted at least $100 from families' payments if children have low school attendance. This ordinance resulted in a 30% increase in graduation in three years, a substantial increase. Furthermore, the Las Vegas Paiute Nation deducted funding for jail provision from the offender's payments because the Nation itself does not have a jail and must rent it from other governments. Punishments such as these provide an incentive for morality through a direct link to financial assistance from the payments themselves.[1]

States also benefit from Native American gaming enterprises. States cannot tax reservations, but they can, under IGRA, negotiate a compact and demand compact payments. Tribes usually pay near or less than 10% of profit to states. The state of Michigan earned an estimated$325 million from tribes spanning from 1993-2003.[1]

Laws require a tribe to agree to a state compact if they request one, but the IGRA says nothing about local governments. However, many tribes do negotiate with local governments. They place a strain on traffic and emergency services, and a tribe not uncommonly tries to compensate for that. Native Americans pay $50 million annually to local governments across the nation. In addition, non-Natives hold 75% of the 300,000 jobs that belong to Native American gaming.[4]

With gaming profits, the Creek Nation of Oklahoma has built its own hospital staffed by Native American doctors and nurses.[5] Other tribes establish health clinics, dialysis centers, and fitness centers to deal with the problem of Native American disease and epidemics. Many tribes work toward securing hope for the future by improving schools. The Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe built two schools that teach fluency in English as well as Ojibwe language.[4]

Failure[edit]

There have been many past attempts to revitalize Native American economies, but most of them have failed. Two of the more successful ventures, besides gaming, include selling gasoline and cigarettes for a much lower price than can be found off the reservation. Tribes are able to sell cheaper goods because there is no state tax. Lower prices draw in non-Natives from off-reservation sites, and tribes are able to earn a considerable profit. Seminole annual income grew from $600,000 in 1968 to $4.5 million in 1977. Smokeshops account for most of this substantial increase. Less effective efforts by the Seminole Nation to boost the economy include cattle raising, craft selling, and alligator wrestling.[2] Cattle operations are popular among the Seminole tribe: with their 7,000 head herd, Seminoles are the largest cattle operators in the state of Florida and the twelfth largest in the United States. However, cattle operations are not overwhelmingly successful because they have been known to benefit the individual rather than the tribe. In addition, cattle operations led to government dependency and debt. Another economic endeavor is craft sales. Some individuals create traditional Seminole crafts and sell them, but this market does not leave a huge impact on the tribal economy. Instead, it benefits the individual as a supplementary income. Alligator wrestling is yet another moneymaker but is not relied upon. Alligator wrestling originated in the 1920s and became synonymous with Seminole culture. It has been denigrated as exploitative, though, and is quite risky. Consequently, alligator wrestling has become less prevalent with the growing popularity of Native American gaming.[2]

If a Native American casino is unsuccessful, its failure is often linked to its geographic location. The size of a tribe is usually insignificant. This argument follows the logic of a free market economy. Tribes with a strong economic base find it easier to draw in new businesses and consumers. Tribes in remote locations suffer because they lack a consumer base to support new and existing businesses.[4] For example, the Morongo Band of Mission Indians is very small, but their gaming enterprises are overwhelmingly successful. In contrast, the Sioux Nation, a very large nation, has struggled to achieve success with gaming enterprises. Regardless of its thousands of members and approximately 12 gambling halls, the Sioux Nation is unable to benefit from gaming enterprises because it is too isolated from potential customers. Another example is found in San Diego County. Four tribes in San Diego County had ambitious plans for a $100 million-plus resort and convention center but preemptively scaled back this idea because they are in an inconvenient location. Far away from other civilization and in close proximity to each other, the tribes concluded their chances of an overwhelming success were slim.[5]

The Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, the second largest reservation in the United States, suffers from extreme poverty. It is the poorest county in the United States and has attempted to revitalize its economy through the gambling industry. However, these attempts have failed. Its casino created a mere 80 jobs,[4] but this figure is insignificant since the unemployment rate on the reservation is up to 95%. The reservation has higher unemployment, diabetes, infant mortality, teen suicide, dropout, and alcoholism rates than the country on a whole. Many homes are dilapidated, overcrowded, and without water, plumbing, and electricity. Pine Ridge's failed attempts are predictable considering the closest major city, Denver, Colorado, is 350 miles away.[9]

Impact on native cultures[edit]

With Native American gaming has come the image of a 'rich Indian.' This depiction contrasts other images of Native Americans portrayed as savage, pure, connected to nature, and spiritual. The reality (that some Native Americans are powerful entrepreneurs) contradicts the notion of what a Native American is 'supposed to be.' 'Rich Indian' propaganda even circulated in response to Proposition 5 in California in 1998[5] that perpetuated the stereotype that 'the only good Indian is a poor Indian.'[10]

Eve Darian-Smith and others have asserted that the impact of gaming on Indian culture in general is a loss of a cultural myth. According to Ronald Wright, these ideas are based on stereotypes and are 'construed by the dominant society in an effort to control and justify the enduring inequalities and injustices that permeate our legal system and social landscape.'[5] One perspective is that Native American gaming is not so much damaging Native culture as it is merely changing a cultural myth, the way the general population perceives Native Americans. Additionally, Native American gaming can be viewed as a means to rejuvenate and preserve tribal culture. For instance, many tribes use revenues generated from gaming toward museums and cultural centers. Tribes are not only able to fund themselves independently but can also afford to preserve their individual histories.[5]

Controversy[edit]

Morality of Native American gaming[edit]

There is some controversy of Native American gambling because it is argued that it contributes to a moral decay. Gambling, it is argued, promotes crime and pathological behavior.[5]Gambling addictions as well as drug and alcohol abuse are sometimes associated with Native American gaming. In 1962, the total estimated sums in the United States totaled $2 billion. This figure jumped to $18 billion in 1976, to $80 billion in 1985, and to $400 billion in 1993. In 2000, the total estimated sums wagered in the United States was $866 billion. In 2000, the commercial take was 10%, so the gaming industry earned approximately $70 billion, even accounting for the fact that gamblers win some money back. That is over three times the $22 billion in total revenues generated by all other forms of entertainment combined: tickets to movies, plays, concerts, performances, and sports events. Moreover, Native American gaming contributes to only a fraction of gambling in the United States. Native American casinos bring in only 17% of gambling revenue, while non-Native casinos raise 43%.[5]

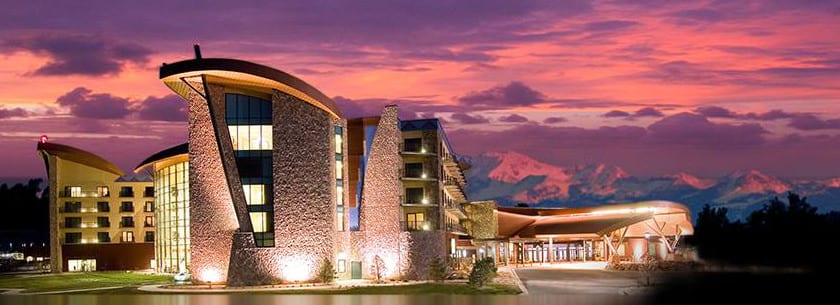

Casinos And Indian Reservations Reservation

TIME magazine controversy[edit]

In late 2002, TIME magazine printed a special report entitled 'Indian Casinos: Wheel of Misfortune' that infuriated Native Americans nationwide. Ernie Stevens, Jr., Chairman of the National Indian Gaming Association, wrote a letter to the editor of TIME in response to the report.[4]

Native American gaming in popular culture[edit]

Native American gaming has appeared many times in literature. The first appearance of Native American gaming was in John Rollin Ridge's 1854 novel The Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta. Christal Quintasket wrote about Native American gaming in her 1927 novel Cogewea, the Half-Blood. Gerald Vizenor writes on this theme in Bearheart: The Heirship Chronicles,The Heirs of Columbus, and Dead Voices. Leslie Marmon Silko wrote a 1977 novel called Ceremony that focuses on gambling. Louise Erdrich, a prominent Native American author, wrote Love Medicine, Tracks, and The Bingo Palace. Traditional, ritual gaming is a common theme in these pieces of literature and provide literary, rather than fact-based, accounts of Native American gaming.[11]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ abcdefgHarvard. The State of the Native Nations. New York: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

- ^ abcCattelino, Jessica R. High Stakes: Florida Seminole Gaming and Sovereignty. Durham: Duke UP, 2008. Print.

- ^Harvard. The State of the Native Nations. New York: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.5

- ^ abcdefStevens, Jr., Ernest L. (December 10, 2002). 'NIGA RESPONDS TO TIME ARTICLE'. Minnesota Indian Gaming Association. Archived from the original on May 30, 2006. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- ^ abcdefghDarian-Smith, Eve. New Capitalists: Law, Politics, and Identity Surrounding Casino Gaming on Native American Land. Belmont: Thomson Wadsworth, 2004. Print.

- ^ abWaldman, Carl. Atlas of The North American Indian. 3rd ed. New York: Infobase, 2009. Print.

- ^SMITH 8

- ^Waldman, Carl. Atlas of The North American Indian. 3rd ed. New York: Infobase, 2009. Print. 281

- ^Schwartz, Stephanie M. 'WAMBLI HO, VOICE OF THE EAGLES: SPECIAL REPORT.' Native Village. 2002. Web. 11 Oct. 2009. .

- ^Los Angeles Times, October 27, 1998

- ^Pasquaretta, Paul. Gambling and Survival in Native North America. Tucson: The University of Arizona, 2003. Print.

Casinos And Indian Reservations

ArchiveCasinos And Indian Reservations Buffet

NATIONAL GAMBLING IMPACT STUDY |